I’m very proud of our team’s thoughtful approach to creating long-lasting connections between people and the lake, and the strategic framework laid out to guide the region toward a prosperous future. I’m proud that our hard work was recognized with a second-place finish in this important international competition. But it didn’t come easily. With teammates, consultants and advisors spread out across the U.S., Czech Republic and Italy, we had to be just as intentional and sincere about the connections we created with each other. Global collaboration is not new to us. Global collaboration during a pandemic is.

COVID-19 eliminated our typical ability to travel, gather as a team, and charrette around a table for hours if not days. Because we could only meet virtually, it also exaggerated the usual learning curve of getting to know each other and the ways we work, think and design. But we worked through it, and ultimately the pandemic became a bigger opportunity than a challenge. Our virtual connections erased geographic boundaries and reduced costs. We’d all been working virtually for months and had adopted new habits by the time this competition was announced in June 2020, but bringing such a big global team together helped us push further into even more innovative ways of working.

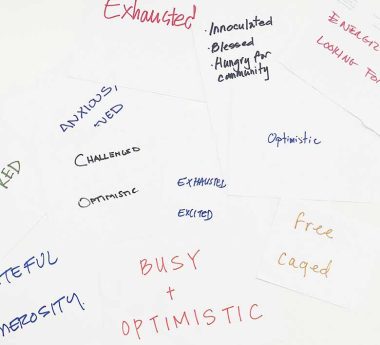

We started using Miro, an online whiteboard platform, and this became a game changer. Layering Miro into our (many) Zoom meetings gave us the tools we needed to facilitate virtual charrettes and workshops, as well as continuous collaboration when we weren’t connected live. In fact, it turned our various time zones into an asset and enabled us to embrace the 24-hour work cycle as a global team. We could schedule meetings strategically so we were getting feedback at the start of our day and at the end of our European counterparts’ day, and vice versa. As we wrapped up our day, we would pass the baton back to them. This proved so effective that we are now using Miro for other Civitas projects and for virtual collaboration both internally as we strategize about our return to the workplace and externally as we connect with clients all over the world.

I’m proud of this process, and even more proud of the powerful impact we can have by participating in programs like this one at Lake Milada. The results give us the confidence to pursue other similar opportunities, and reinforce our belief that we—Civitas—can affect change at a global scale.

Congratulations to the entire team of collaborators, including: 4ct, Atelier of Landscape Architecture Sendler, collcoll, mobility in chain, and Populous.